Luo Yang × Nagashima Yurie: Contemporary East Asian photography and the portraiture of the common ground

This dissertation was written as part of my MA Photography programme at the Royal College of Art in 2018. It was awarded a distinction, and a printed copy is kept at the RCA Library.

Written under the supervision of Jessica Potter.

A note on names: This text deals with Chinese and Japanese photography, and thus mentions many Chinese and Japanese names. It is customary to write names in those cultures with the surname followed by the given name. Thus, in Luo Yang’s case, Luo is her surname, and Yang is her given name. The same goes for Nagashima Yurie: Nagashima is the surname and Yurie is the given name. However, the reverse order, more common in the West, has been preserved in quotes, citations, and titles of referenced publications.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to extend special thanks to Dr. Eva Morawietz, art historian and director of the popup gallery MO-Industries, for her help and patience during the research and writing of this dissertation.

Introduction

In this dissertation, I will examine a certain type of portraiture and the associated aesthetic, through the lens of two female East Asian photographers. One, Nagashima Yurie, came to prominence in Japan in the early 1990s, and the other, Luo Yang, has been building a reputation outside of her native China with several exhibition in the West since being selected as one of the “rising stars of Chinese photography” by renowned artist Ai Weiwei in 20121.

I will tentatively call the style these two artists work in the portraiture of the common ground, and, by the conclusion of this text, we will hopefully have arrived at a definition of this style, within the historical, cultural, and social context in which it has evolved.

The portraiture style in question has blurred boundaries and is maybe easiest to talk about in terms of what it is not. It is not formal: the people are often portrayed in everyday situations and in mundane settings, and the stories told in the photographs are those of real people inhabiting the real world. It is not technically elaborate: photographers eschew complex studio lighting setups and rely on available light or simple on-camera flash to illuminate their pictures. It is not aggressive: even when the photographs are not candid, the subjects are rarely felt projecting any kind of hostility, and any strength displayed is often of the soft and quietly confident kind. However, the portraiture of the common ground goes beyond the visual style and is related both to the subject matter itself and the ways to approach it.

The research contained in this dissertation is coloured by my own background and interests, as well as by my professional practice. I am an immigrant, born in Russian and having grown up in France, with the notion of common ground omnipresent in my life and in my work. I am primarily a portrait photographer, working, and, having spent six years living and practising photography in Japan, this country and its portrait photographers were the start of the series of inquiries that led to me exploring this topic. I became familiar Chinese photography much later, and became so impressed with the work of Chinese photographers, and with that of Luo Yang specifically, that I have since travelled to China and have initiated several related photographic projects, the first of which will be produced in the summer of 2018.

In addition to exploring Luo’s and Nagashima’s work and the parallels between them, I will attempt to offer a brief overview of the emergence of these artists, and the social and historic context in which their work has developed in their native China and Japan.

Origins of Japan’s photographic renewal

In the context of Japanese photography, the aesthetics shared by Nagashima and her peers are very much a product of their time and of social, economic, and political upheaval of the 1990s and 2000s.

Japanese photography after the end of the Second World War has a rich history, marked by three milestones: the renewal of the military alliance with the United States of America (安保, Anpo) in 1960, the Tokyo Olympic Games of 1964, and the bursting of the Bubble Economy in 1991.

The intense political confrontation around Anpo, which marked the end of American post-war occupation and set the framework for (among others) the presence of American military bases in Japan that continues to this day, infused a new and electrifyingly heightened political consciousness into Japanese photographers, artists and intellectuals. So strong was this influence that its echoes continue to be felt this day, not unlike those of the 1968 student protests in France.

The 1964 Olympic games were followed by a period of high economic growth, in which photography, as an art, developed significantly. Economic growth meant a rise in volume for advertising and commercial photography, leading to tackling of experimental techniques and experimentation on a much wider scale. At the same time, documentary work blossomed through photographers focusing on the the newly emerging mass society and its contradiction, as well as through Japanese photojournalists sent to cover the war in Vietnam, most notably Sawada Kyōichi, who won the 1965 World Press Photo of the Year award and the Pulitzer Prize for his picture of a mother escaping a US bombing with her children (Fig. 1). The photojournalists having paved the way, more and more “Japanese photographers spent extended periods of time overseas and became active on the international stage”.2

The emergence of mass society meant that photography became omnipresent: photographing and being photographed became a part of everyday life, and at the same time led photographers to join a growing, radical questioning of the post-war established political, cultural, and economic order. In the late 1960s, Japan was rocked by waves of student protests, which led to what is could be considered the peak of Japanese post-war photography, and the decade that followed is probably what Japanese photography is best known for in the West.

In late 1968, Taki Koji, Nakahira Takuma, Takanashi Yutaka, and Okada Takahiro established a magazine named Provoke, and were joined a year later by Moriyama Daido.3 The aesthetic developed by the Provoke photographers, also known as are, bure, boke (rough, blurry, out of focus) (see Fig. 2), has endured and became recognisable world wide, along with the names of the magazine’s founders — Moriyama, in particular, is arguably the Japanese photographer currently best known to the Western mainstream.

The Provoke aesthetic was born out of the furious anti-American, anti-establishment protest culture of the Japanese 1960s, and it served the purpose of the photographers who established the magazine: to bring down established conventions and to create a new visual language, “to rethink the rigidified relation between word and image”.4

In the afterword to the first issue, Provoke’s Nakahira Takuma writes:

“How to fill the gap between politics and art? This is both an old and a new problem. . . . . My belief is to accept the contradiction between political matters and the act of creating something, and try to live with the tension between them. This is my personal position, and I would like to operate whilst considering the two things separately – to participate actively in the political struggle, and to take photographs, in a dualistic way”.5

To understand the context in which the work of Nagashima Yurie and her aesthetic has emerged, one must look at the political and economical history of post-war Japan, and what changed from the Provoke era. After the anti-American, anti-capitalist protests of the 60s and 70s, Japan’s center-right-wing government has found an innovative way to de-claw the Left, and especially its more radical wing: by satisfying their demands. The emergence of the practice of lifetime employment meant that workers were assured of financial stability for themselves and their families, in exchange for loyalty to the companies employing them, which in turn became a secondary (and sometimes primary) family for them. This system helped bring about the Economic Miracle, which saw Japan’s economy rise to be second only to that of the US. This, however, came to an end in late 1991 when the asset price bubble burst, triggering an economic decline that would last over a decade. The public protest culture having been largely lost thanks to the comforts of a growing economy and lifetime employment, photographers who came of age during this “Lost Decades” naturally focused more inward, exploring and finding beauty in a slower, more contemplative life, which in turn reflects the aesthetic they have developed.

The aesthetic of Nagashima and her peers started to work in in the 1990s stands in stark contrast to that of the Provoke photographers. It is, in fact, very much on the opposite side of the spectrum: muted colours as opposed to the intense, often violent, high contrast black and white, and a focus turned to private spaces instead of a revolutionary desire to bring down established conventions and to create a new visual language.

Another defining characteristic of the style that Nagashima works in is the large part that female photographers played in its development. While in the Provoke era and subsequent decades Japanese photography was overwhelmingly male-dominated, many of the defining photographers working in this new aesthetic are female. Along with Nagashima, Hiromix (see Fig. 3), Ninagawa Mika, Kawauchi Rinko, Ume Kayo, and many others contributed to the development of this style, and paved the way to countless more photographers.

It is also not my intention to imply that the work of Japanese female photographers of the mid-90s is any less radical than that of the men of the are, bure, boke era: the battleground has moved from the streets to their own private spaces, and their own bodies within those spaces. The confrontation was no longer “an ideological clash with the state, but it was a political clash with the various media that construct female identity”6.

For Nagashima and her cohorts, the act of photography “fostered the affirmation of social and self identities that they were comfortable with, a shield against the pressures to conform to social and familial expectations.”7 “To push their way through these barriers and face their inner selves for self-identification, they happened to have the tool of photography”.8

Nagashima Yurie

Nagashima was born in 1973 and rose to prominence through a series representing herself and her family in the nude, winning the prestigious PARCO prize in 1993 while a student at the Musashino Art University9.

Just as with Toshikawa Hiromi (also known as Hiromix, another female photographer figurehead of the 90s), Nagashima’s visual style has initially been derided as simplistic and amateurish, “in sharp contrast with a type of photography, popular in the 1980s, in which image-making was considered a technical craft”10. Dismissively labeled by critic Iizawa Kōtarō as “girly photography” (女の子写真, onnanoko shashin), the movement spearheaded by Nagashima is characterised, from a technical point of view, by its welcoming of imperfection in photographs.

The photographers embraced film stock and cameras considered as amateur and eschew complex technical processes. They favoured small, compact cameras: easy to carry around, usually with a built-in flash, strong automation features, and a moderately wide angle lens, often around 35mm. Asked about the way she photographs, Kayo Ume (another prominent member of the movement) says: “I always set my camera at P mode. They say P stands for ‘programme’11 but I call it ‘professional mode’.”12 The result is often featuring strong colours (sometimes accentuated even further by direct flash), natural light, and sometimes chaotic composition. Just like with the Provoke style, an immediacy and a participation in the moment is privileged over high-level technique or composition, what photographer John Sypal refers to as being about the “actual living moment and using the camera to interact with it”.13

In another parallel to the photographers of the Provoke era, then, a rejection of photography as a highly technical craft is a strong feature of the style espoused by Nagashima. However, while the Provoke photographers focused on conflict with the state, Nagashima and the members of her movement turn their lenses closer to home: close friends, family, and loved ones are frequent subjects of their photographs. Quoting the famous second-wave feminist rallying slogan, Nagashima says: “I believe, ‘Personal is political’”14

Nagashima is widely considered to be the photographer whose work launched the onnanoko shashin movement, and it is that specific style that brought her stardom at home and, to some degree, recognition abroad. She, however, rejected term and resented Iizawa for coining it, as it implied a lack of agency and skills on the part of the photographers: “we didn’t choose snapshot photography because of a lack of skills, or because we weren’t physically strong enough to handle larger camera equipment. It was because the portability of those cameras suited our work, and this explanation made perfect sense”15. When Nagashima received the Kimura Ihei Award (one of Japan’s highest distinctions for photographers) in 2000, the prize was given to three photographers together, the others being Hiromix and Ninagawa Mika. Nagashima felt that the Japanese art world felt “as if [they] all belonged in that [onnanoko shashin] category”16, interpreting the work in a “light, pop-culture sense”17 and ignoring its feminist message.

That feminist message is strongly present even in the the debut project that brought Nagashima recognition in Japan, her nude self-portraits with her family. Talking at a panel at Art Basel 2018 in Hong Kong, Nagashima explains:

I felt like I myself was a kind of object, therefore I thought that I had to change, I had to express something that was different. My body is my own, it’s not the object of the male, that’s what I wanted to express, and that’s why I came up with the self-portrait series, which is the nude photos of my family. In the 1990s, in the United States at that time there was the Third Wave of feminism that started, for example the Riot Grrrl movement, in music, and in fashion, through these cultures there was a new feminism, and we get a lot of influence by these movements.18

In the same panel, Nagashima Yurie clearly declares: “I am a feminist”.19

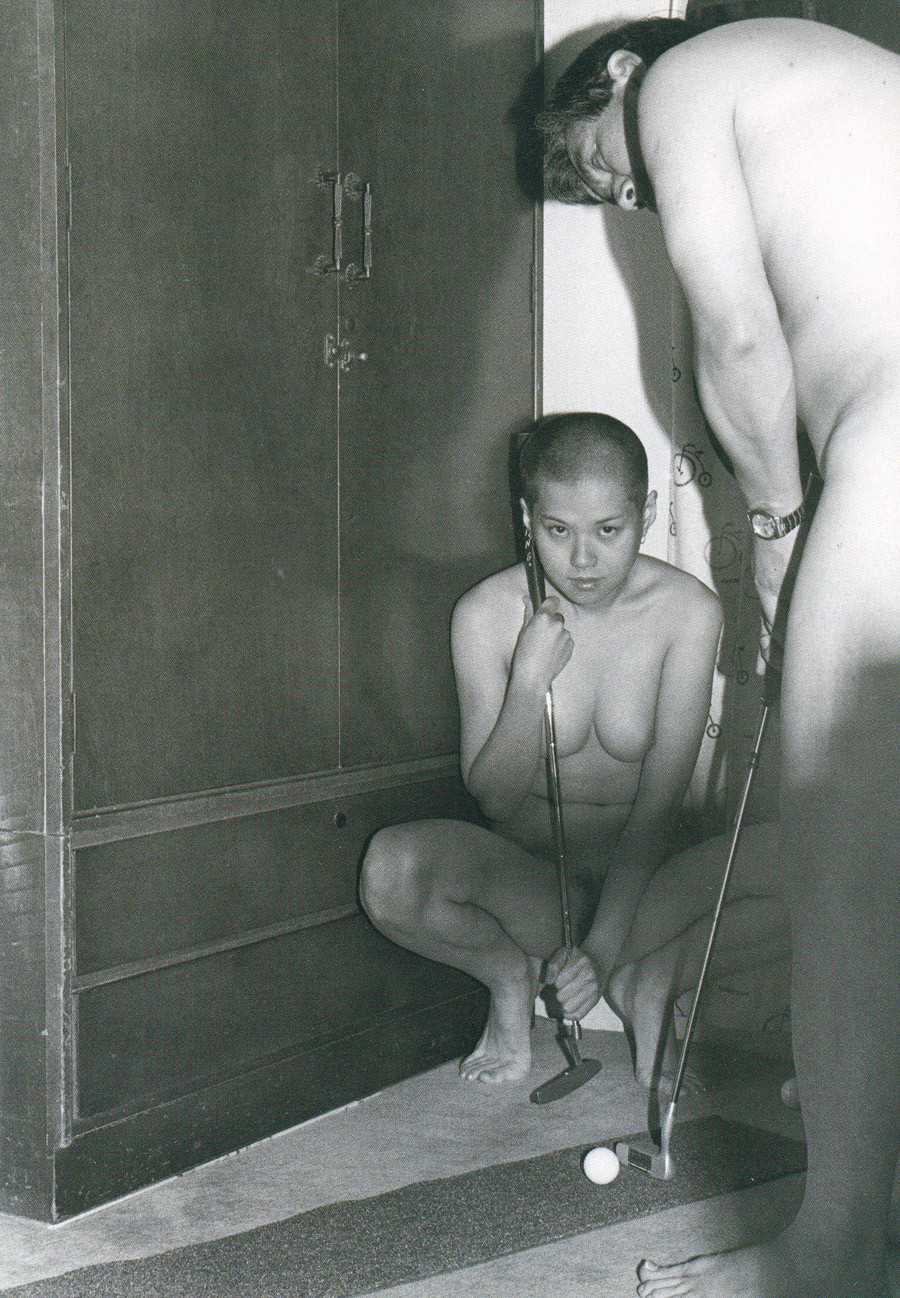

The same assertions of agency and individuality permeate the projects Nagashima has worked on since, in which she continues to explore family, loved ones, and inner circles. In the monograph Not six (Tokyo: Switch Publishing, 2005), she shows seven years worth of photographs of her husband, reversing the more traditional photographer/model gender roles. (Fig. 6). In Pastime Paradise (Tokyo: MADRA publishing, 2000), Nagashima’s record of her life between her rise to fame and her return to Japan after a few years of studying in the US are reminiscent of one of her major influences, Nan Goldin, another feminist photographer. With 5 Comes After 6 (Tokyo: MATCH and Company, 2014), Nagashima chronicles her son’s childhood and life as a single mother and a photographer, following a split with her partner.

Moving forward, Nagashima is interested in exploring the stories of women who gave up dreams in order to take care of families and children.20

The rise of unofficial photography in China

Luo Yang (b. 1984) is part of a new generation of photographers that is giving Chinese photography a well-established identity on the global scale. In order to understand the context in which she produces her work, a brief look in the history of Chinese photography in the 20th century is necessary.

During Mao’s era, in the upheavals of the Great Leap Forward (1959-1962) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) photography was given a purely propagandist role, serving the state’s goals of generating popular compliance with party policies.

In one striking photograph taken during the Great Leap Forward famine — which claimed upwards of thirty million lives — a group of children are depicted apparently standing on top of a field of wheat, apparently so densely grown that it could support their weight21. (Fig. 722) The children were in fact standing on top of a bench concealed by the especially arranged stalks.

Unofficial photography started to emerge into the public view in the the aftermath of the death of Premier Zhou Enlai in 1976, with amateur photographers spontaneously documenting the the public mourning for the popular politician on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a mourning officially forbidden by the authorities. Wang Zhiping, Li Xiaobin, Wang Miao, and the other photographers of the April 5th Movement — as the event became known — later became the leaders of the Photographic New Wave of the 1980s.23

Though the work of these photographers began outside of the system, they unexpectedly found themselves thrust into the mainstream of Chinese photography: a compilation of photographs of the April 5th Movement the photographers published in 1979 under the name of “People’s Mourning” (人民的悼念, rénmín de dàoniàn) received an unexpected endorsement from China’s top leadership following the end of the Cultural Revolution and the fall of the Gang of Four24, with the new Party Chairman, Hua Guofeng, authoring a dedication on the book’s title page, and the editors being invited to join the mainstream Association of Chinese Photographers.25

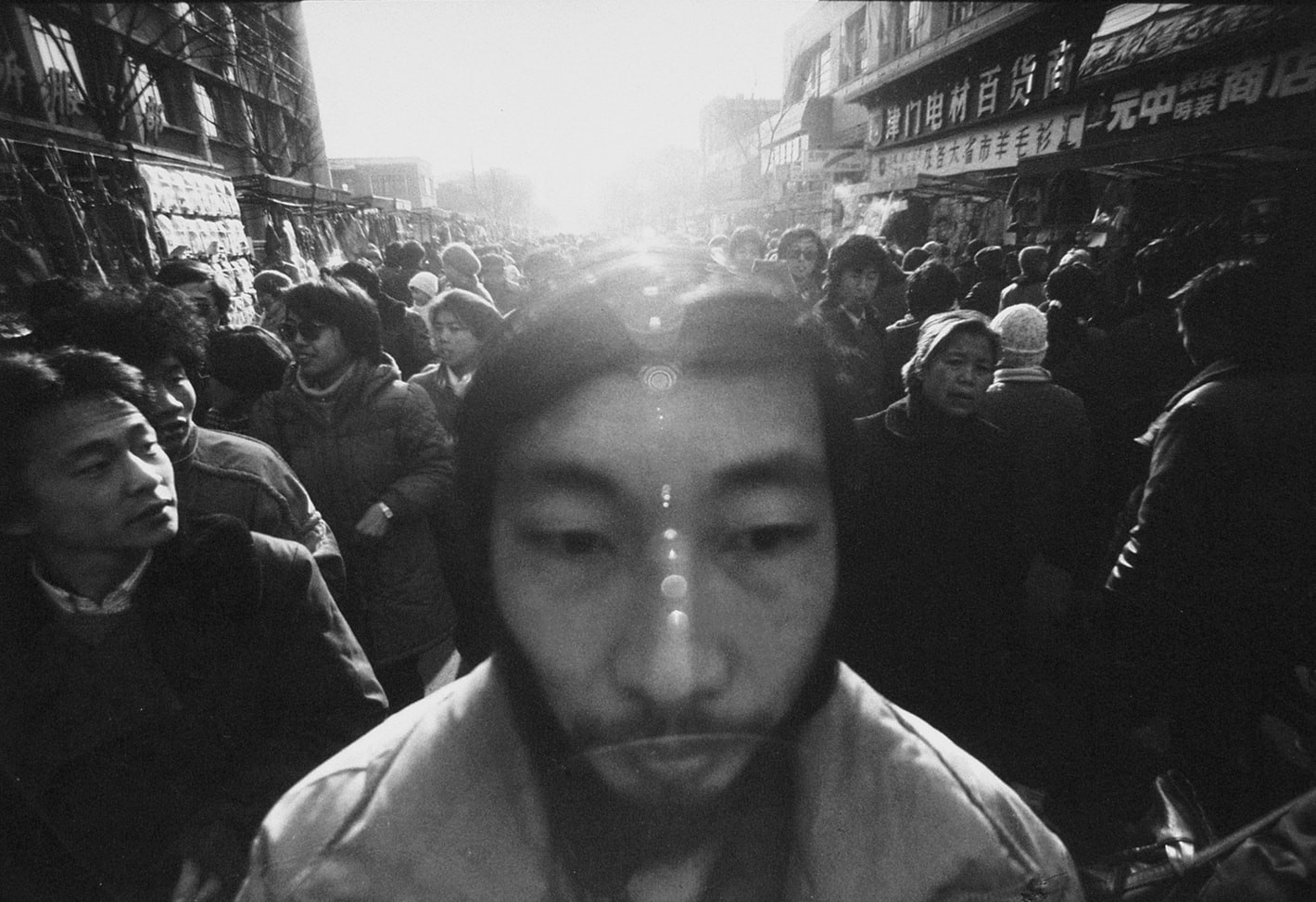

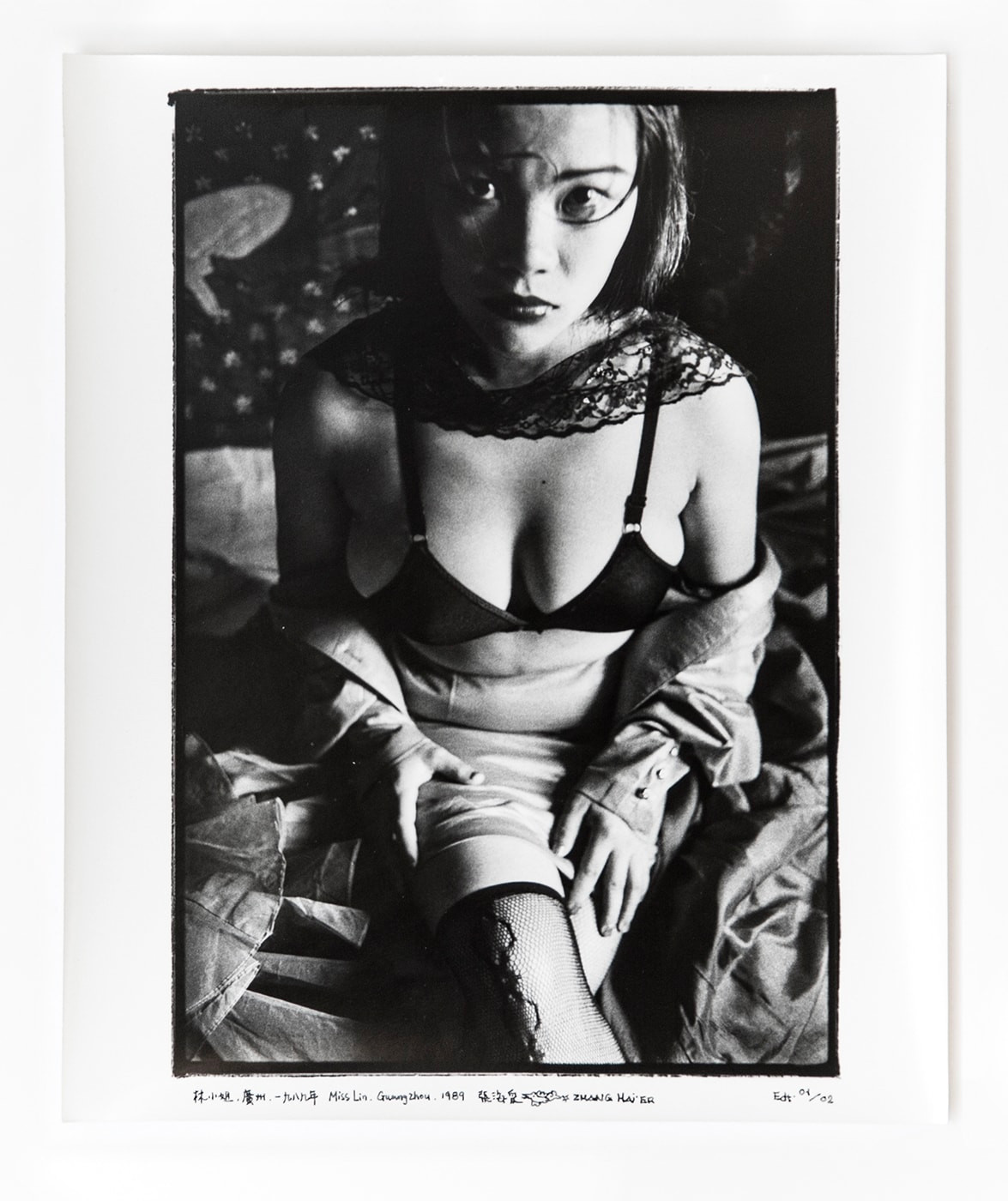

Disillusioned with the official hijacking of their project, the April 5th photographers turned away from politics and towards more aesthetic pursuits, organising several unofficial exhibitions on the theme of Nature, Society, and Man26. While the first of those was held only in Beijing, its success prompted the following two editions to appear around China, triggering a nationwide movement known as the Photographic New Wave in 1981. This movement saw the creation of a large number of photography clubs and publications, a widespread interest in works of Western photographers and the documentary genre, and the emergence of photographers such as Mo Yi (fig. 3) and Zhang Hai’er (fig. 4), who responded to the rapid transformation of Chinese cities by developing “new concepts and languages that allowed them not only to represent an external reality but also to respond to reality”.27

Towards the end of the 90’s, the New Wave movement has allowed a new kind of photography to emerge, “that allied itself with the burgeoning avant-garde art”28, which caught the attention of the international art world, with Zhang Hai’er and others being invited to the Arles festival in France in 1988. However, this period of growth was cut short by a political event: the violent suppression by the government of pro-democracy student demonstration in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 (also known as the June 4th movement). Following the crackdown, avant-garde art was banned and for a few years no controversial work could be shown.

The new generation of photographers, defining what would come to be known as Experimental Photography (实验摄影, shìyàn shèyǐng), emerged in the early-to-mid 90s. They had developed completely outside of the mainstream institutions — schools, research institutes, galleries — of Chinese photography. These young photographers were outsiders from the mainstream of Chinese photography and “constituted a sub-group within the camp of experimental artists (…) they lived and worked with experimental artists, and showed their work almost exclusively in unofficial experimental art exhibitions.”29

One of the defining events of this experimental age was the appearance of new types of experimental art publications, one of the most important ones being The Book With a Black Cover (黑皮书, hēipí shū) published in 1994 by experimental artists including Ai Weiwei. The book introduced the new generation of Chinese experimental artists to the world, with photography being featured as the most important medium of experimental art.

Conceptual photography developed, relying on theories of postmodernism, which led Wu Hung comparing the emphasis on concept and display with American conceptual photography of the 1970s, described by the poet and art historian Corinne Robins in these words:30

Photographers concentrated on making up or creating scenes for the camera in terms of their own inner vision. To them . . . realism belonged to the earlier history of photography and, as seventies artists, they embarked on a different kind of aesthetic quest. It was not, however, the romantic symbolism of photography of the 1920s and 1930s, with its emphasis on the abstract beauty of the object, that had caught their attention, but rather a new kind of concentration on narrative drama, on the depiction of time changes in the camera’s fictional movement. The photograph, instead of being presented as a depiction of reality, was now something created to show us things that were felt rather than necessarily seen.31

With Ai Weiwei’s rise to prominence, conceptual and experimental art continued to develop, leading to the seminal 2000 exhibition Fuck Off (不合作方式, bù hézuò fāngshì [“Uncooperative Attitude”]) curated by, among others, Ai. In a conversation with Chin-Chin Yap, Ai Weiwei links the exhibition with the Book With a Black Cover:

Chin-Chin Yap: When you curated Fuck Off in 2000, was there a similar concept behind it as with the books?32

Ai Weiwei: Yes, after these three books we stopped, and a few years later there were quite a lot of art events happening and interesting works around, so people suggested having a show with a similar sort of attitude as that of the books. So we thought about putting on an exhibition. It wasn’t necessarily the best show because we had to put it together in a very short time, and the conditions were such that the police could shut it down at any moment and everything taken away. But the artists were very cooperative and interested and the attitude was there. The show’s still being talked about today, because it’s an attitude that still matters. So maybe Fuck Off was most important because of what it represented. The concept was clear; and we were very clear about what we wanted to say towards Chinese institutions as well as Western curators and institutions and dealers; their functions are all similar in one way or the other. It’s all about the deal, about labour, how to trademark different interests. We had to say some thing as individual artists to the outside world, and what we said was “fuck off.”33

Fuck Off was shut down by the Shanghai police before the closing date, but the exhibition went on to acquire a legendary status among China’s younger artists. It was followed up on in 2013 by Fuck Off 2, which Ai co-curated in Groninger Museum in the city of Groningen in the northern Netherlands. This exhibition was introduced by the museum as a “show, which includes 37 contemporary Chinese artists and artist groups, contemplates and questions the current sociological, environmental, legal, and political climate in China today.”34. The museum’s blurb goes on: “The exhibition is a sequel to Fuck Off, the ground-breaking show staged in Shanghai in 2000 by Ai Weiwei and Feng Boyi, which was quickly censored by the authorities as it was considered too sensitive with its radical content. Thirteen years later, the lack of artistic freedom in China and the repressive attitude toward individual actions by the government make Fuck Off 2 especially relevant today.”35

Along with other contemporary Chinese artists (some, such as Ren Hang, already internationally acclaimed), Fuck Off 2 introduced international audiences to the work of Luo Yang. m “Photography 2013 II”. © Ren Hang

Luo Yang

Luo Yang was born in 1984 in Shenyang, capital of the northern Chinese province of Liaoning. She studied graphic design at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, from which she graduated in 2009. Luo started photographing in 2007 while in university, taking pictures of her friends — “the life of those girls who were around me”.36 Out of this process came the project Girls, which Luo developed over the next decade, and which was published as a book by Edition Lammerhuber and MO-Industries in 2017.

Having been born a few years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, Luo grew up at a time when China was just starting to open up to Western influences: “Luo’s generation grew up in a realm of confused cultural constructs, with strong traces of traditional culture intermingling with new and invasive Western ideas — all at a pace that was far surpassed by the speed of economic change swirling around it”.37 The effect of this uneasy time are well visible in the work of Luo’s peers: photographers Ren Hang, Lin Zhipeng, and Chen Zhe (all of them fellow participants in Fuck Off 2) and novelist Chun Shu, whose novel, Beijing Doll (Riverhead Books, 2004), chronicles growing up in Beijing of the 1990s.

In the introduction to the “Girls” book, art historian Eva Morawietz writes:

The term GIRLS in Luo’s work thus refers to young women who are in the process of forming their identity. It denotes a state of mind, rather than a specific point in life, although Luo prefers to shoot women who are close to her own age. She started the project in 2007 when she was attending university and considered herself a ‘young girl’. The series has evolved alongside Luo and her life, spanning a timeframe of ten years until today. Her models have grown from girls to women and even to young mothers, who joined the series most recently. Just like herself, Luo’s GIRLS have often migrated from rural areas to the large cities, from Norther China and Liaoning, Luo’s home province to Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu or Chongqing. Today, Luo travels all over China to photograph women from various backgrounds and ages.38

The time scale and geographical reach of Luo’s work makes Girls a pioneering project. According to Morawietz: “To date, Luo’s GIRLS series is a first long-term venture into the portrayal of young Chinese women created by a Chinese woman, showcasing the plurality of female identity in contemporary China.”39 That is not to say that Luo is the first female Chinese photographer working on questions of femininity or representing a female point of view. Some notable precursors are artists Xing Danwen (b. 1967, Born with the Cultural Revolution) and Chen Lingyang (b. 1975, Twelve Flowers Series).

The aesthetics of Luo’s work, as well as those of her peers, can be reminiscent of Western photographers Wolfgang Tilmans or Jürgen Teller. Luo also considers Rineke Dijkstra, Ana Mendieta, and Nan Goldin as having had influence on her work, as well as Japanese photographers Moriyama Daido and Nagashima Yurie.40

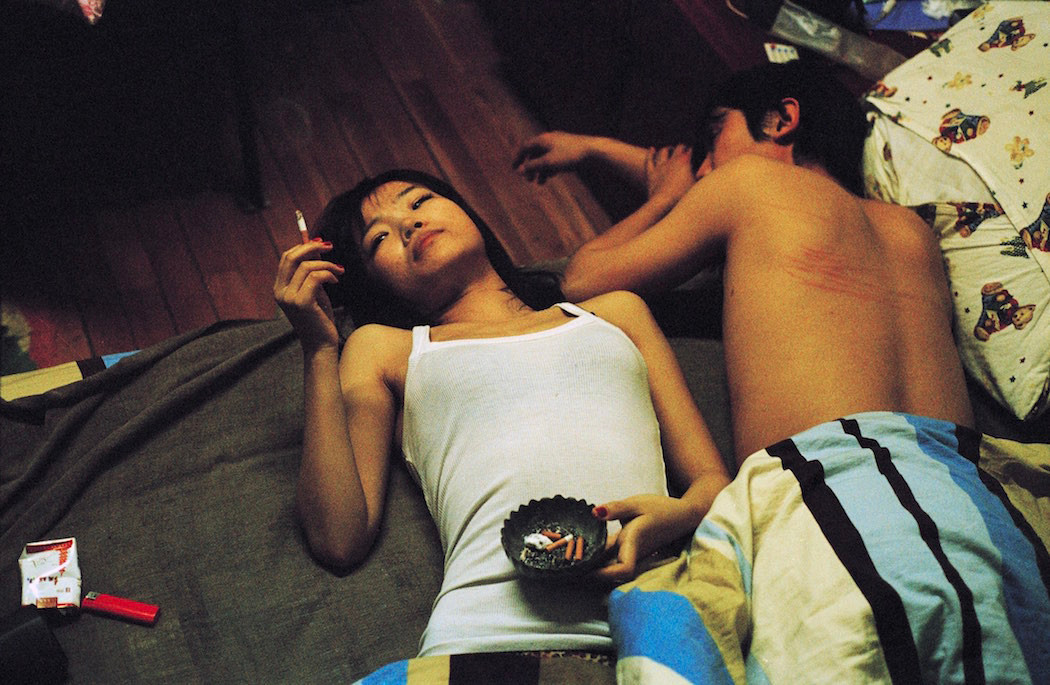

Like Nagashima’s work, Luo Yang’s photography is done with film, and eschews technical perfection in favour of a sense of reality and of strong connection with her models, the eponymous Girls. Even though Girls is a portraiture project, focusing on both friends and strangers rather than herself, the connection and the relationship the photographer has with her models brings out the autobiographical qualities of the work.

The women in Girls belong to the same generation as Luo — with the same post-Cultural revolution roots — and have grown up together with her over the ten years the project has been unfolding. Eva Morawietz describes the project as focused on “the tough process of inner growth in a reality ground in friction, full of hope and latent crisis”41.

In an interview with Spiegel Online, Luo mentions that she “always has the feeling that she’s showing something of herself when (she) portrays other women”42. She goes on to mention the kind of personalities that attract her for the project: “Women who are different, who rebel against the rules and who don’t live a standard life, women who have ideals”,4344 qualities the photographer — beyond associating them with herself — wants to showcase as the main point of her project. Morawietz writes:

“GIRLS are about pure female ego, about showing oneself as a woman, expressing individuality and pursuing an independent life based on one’s own choices, regardless of traditional expectations, stereotypes or modern-day social pressures.45[…] the disarming display of the GIRLS’ fragilities becomes a powerful marker of unrelenting personal autonomy. Their evident candour presents itself as a metaphor for freedom and independence.”46

When asked about the political aspect of her work, Luo and her peers are eager to insist that their work has “nothing to do with politics directly”47, and that they are focused on the individual. According to Morawietz, Luo’s work is “very personal, it’s intimate, it’s about individuality, it’s about emotions, it’s about expressing individuality and authenticity”,48 which, in a country with a history of suppressing the free expression of personal opinions49, is can be seen as an intensely political position in itself.50

In the future, Luo Yang plans to continue working on the project and to develop it further, to include other media, notably video, and collaborations with other artists. She is also interested in focusing on the subject of mothers: “When we were little, in the1980’s, mothers in China went through incredibly hard times, but nobody ever took note of that. The time of our mothers will pass in a near future, it would be a pity to not document their lives.”51 A hint of this can already be seen in the work that’s included as part of Girls, including in a photograph of the twins Wan Ying and Snow Ying (Fig. 14):

This photo was shot in Chongqing. Chongqing is a very magical city, a city with a river of such magnitude, it always fills people with the presence of lots of stories. Of the twins, the younger is a mother whereas the elder sister is still single. They share the same blood, but have significantly different personalities and went in very different directions in life. The relationship between these twins is fantastic, loving one another but also seeing a different version of oneself in each other.52

A portraiture of the common ground

The intention at the beginning of writing of this dissertation was to define a certain visual style common to Luo Yang and Yurie Nagashima, as well as other artists working with the same sensibilities and on similar subject matter. However, what has emerged from researching these photographers and examining their work was beyond mere visuals. The connections between the portraiture work of Luo and Nagashima go beyond the aesthetic similarities and get interesting in the approach to their subject matter exhibited by the two photographers.

That is not to say that the technical aspect is not important for this portraiture of the common ground. Both Nagashima and Luo are primarily users of film cameras. Luo says that “there is a humanising impression in film; it’s rich in both texture and colour. Shooting in film encourages (her) to contemplate more.”53 They both use an array of cameras, in both 35mm and medium format, and they both produce pictures that are candid and others that are carefully constructed. Another characteristic of this style is that neither photographer attempts to construct images beyond what is possible with the model and the environment at hand. Luo, the more directive of the two, might arrange her models in ways that she considers more interesting, but says that “usually the shooting takes place at an environment that they are familiar with, no preparations or particular settings.”54 This lack of artifice (be it in location, lighting, make-up…) gives the bodies of work produced by the two photographers a sense of spontaneity, a sense of a realism of the everyday, which is used in the service of emphasising an intimacy.

Intimacy is a key component of the portraiture of the common ground. Both Luo and Nagashima photograph people close to them. Nagashima photographs her family, her friends, her husband, her son; Luo her friends and girls with whom she feels a sense of kinship, and although she has no blood ties to her subjects, one could imagine them as a sort of extended family she has constructed for herself. The closeness to the subjects that permeates both photographers’ work allows the pictures to emphasise a common ground, a humanity shared on several levels.

That humanity is shared first, via mutual vulnerability, between the photographers and the subjects. Looking at both photographers work, it’s hard not to be struck by the basic human connection between two people that flows through the camera. Thus, the act of photographing becomes an act of acknowledgement and of acceptance from both participants, and, to resort to the old cliché, each photograph becomes a self-portrait.

Beyond this amalgamation between the photographer and the subject, both photographers compellingly highlight their subjects’ individuality, and, through it, their own — quite literally in the case of Nagashima’s self-portraits, and by implication in the case of Luo’s portrait work. This inexorable insistence on personal identity has the effect of pulling the viewer, without necessarily soliciting his or her consent, into the bond of vulnerability, acknowledgement, and acceptance between the photographer and the subject.

Herein lies the might of the portraiture of common ground: the viewer is forced to extricate the person in the photograph from any kind of grouping that preconceived notions about gender, age, ethnicity, or appearance might have placed her in, and to consider her as an individual, with her own hopes, vulnerabilities, successes, failures, and dreams. In other words, to find a common ground with her.

When it comes to the subject matter pursued by Nagashima Yurie and Luo Yang — questions of femininity and the female point of view — this relentless affirmation of individuality can only be political, clashing as it does with the established order in countries that have long traditions of patriarchy and collectivism. The measure to which this feminist attitude is claimed — vocally by Nagashima and implicitly by Luo — could be seen as a barometer for political freedoms in their respective countries, however, the fact that it permeates the work is crucial. The work of Nagashima, Luo, and others working in the same direction is thus, in an era of increased global trends towards xenophobia and isolationism, playing a role not unlike that of golden age photojournalism of the 1950s-70s: promoting a deeply humanist message of peace, acceptance, and a shared humanity that goes far deeper than any differences possibly could.

Bibliography

Books

- Ai, Weiwei, and Charles Merewether, Ai Weiwei: Works, Beijing 1993-2003, 2003

- Bohr, Marco, ‘Deconstructing Gender Identity & Non-Perfection in the Photographs of Yurie Nagashima’, in On Perfection: an Artists Symposium, ed. by Jo Longhurst (Bristol, 2013)

- Dāngdài Zhōngguó cóngshū biānjí bù, ‘Dāngdài Zhōngguó De Tiānjīn [Tianjin in Contemporary China]’, ed. by Dāngdài Zhōngguó cóngshū biānjí bù (1989)

- Friis-Hansen, Dana, ‘Internationalization, Individualism, Institutionalization’, in The History of Japanese Photography(New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press)

- Halliday, Jon, and Jung Chang, Mao: the Unknown Story (Random House, 2012)

- Hung, Wu, Christopher Phillips, International Center of Photography, Between Past and Future (University of Chicago David & Alfred, 2004)

- Iizawa, Kōtarō, ‘The Evolution of Postwar Photography’, in The History of Japanese Photography, ed. by Anne Wilkes Tucker (New Haven, Conn., 2003)

- Iizawa, Kōtarō, ‘The Girls Are in the Room: Women Photographers in the ‘90s’, in Private Room II: Shinsedai No Shashin Hyōgen (Mito, 1999)

- Morawietz, Eva, ‘LUO YANG GIRLS Ambiguous Identities’, in Girls, 2017 (Baden: Edition Lammerhuber, 2017)

- Nakahira, Takuma, ‘Afterword to Purovōku: Shisō No Tame No Chōhatsuteki Shiryō’, in Provoke No. 1 (Tokyo, 1968)

- Robins, Corinne, The Pluralist Era: American Art, 1968-1981 (New York: Harper and Row, 1984)

Online sources

- Ai, Weiwei, ‘Generation Next: a Photo Essay’, New Statesman, 2012 [accessed 21 June 2018]

- Andrews, Blake, ‘Q&A with John Sypal’, B [accessed 21 June 2018]

- Arena, Gianpaolo, ‘Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?’, LANDSCAPE Stories, 2016 [accessed 19 March 2018]

- Arnstein, Tom, ‘Beijing-Based Photographer Luo Yang Shoots to Smash Stereotypes of Chinese Girls’, The Beijinger, 2017 [accessed 20 June 2018]

- Art Basel, ‘Conversations | Artworld Talk | Feminist Aesthetics? Movements and Manifestations’ [YouTube video], 2018 [accessed 19 June 2018]

- Blaj, Patricia Luiza, ‘Luo Yang’s ‘GIRLS’ Shows the Beauty of Vulnerability - the OUTSIDERZ’, The Outsiderz, 2017 [accessed 15 June 2018]

- Groninger Museum, ‘FUCK OFF 2. Curated by Ai Weiwei, Feng Boyi, Mark Wilson’, Groninger Museum, 2013 [accessed 17 June 2018]

- Hernanz, Clara, ‘Luo Yang’s Photos Show Women Rebelling Against Classic Chinese Femininity’, Dazed, 2018 [accessed 19 June 2018]

- Jacquet, Marianne, ‘GIRLS by Luo Yang - an Interview’, Kaltblut, 2016 [accessed 18 June 2018]

- Kalkhof, Maximilian, ‘Chinesische Fotografin Luo Yang: “Wäre Es Okay, Wenn Du Dich Ausziehst?”’, Spiegel Online, 2016 [accessed 15 May 2018]

- Lucas, Julian, ‘LUO YANG: an Exploration of the New Chinese Woman’, Mirrored Society, 2016 [accessed 18 June 2018]

- Pastore, Jennifer, ‘Yurie Nagashima: and a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love’, Tokyo Art Beat, 2017 [accessed 18 May 2018]

- Xu, Beina, and Eleanor Albert, ‘Media Censorship in China’, Council on Foreign Relations, 2017 [accessed 10 June 2018]

- ‘Kayo Ume: Life Cycle’, POCKO, 2015 [accessed 21 March 2018]

- ‘Yurie Nagashima’, Maho Kubota Gallery (Tokyo) [accessed 19 March 2018]

-

Ai Weiwei, ‘Generation next: a photo essay’, New Statesman (Ai Weiwei guest-edit), 22 October 2012 <https://www.newstatesman.com/world-affairs/world-affairs/2012/10/generation-next-photo-essay> [15 June 2018], (para 7 of 12) ↩

-

Iizawa Kōtarō, ‘The Evolution of Postwar Photography’, in The history of Japanese photography, ed. by Anne Wilkes Tucker (New Haven, Conn. : London : Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 208-259 (p. 220) ↩

-

Iizawa, p. 220 ↩

-

Iizawa, p. 220 ↩

-

Nakahira Takuma, Afterword to Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō (Provoke No. 1), (Tokyo: Purovōku-sha, 1968) ↩

-

Marco Bohr, ‘Deconstructing Gender Identity & Non-Perfection in the Photographs of Yurie Nagashima’ in On Perfection: An Artists’ Symposium, ed. by Jo Longhurst (Bristol: Intellect, 2013), p. 368 ↩

-

Dana Friis-Hansen, ‘Internationalization, Individualism, Institutionalization’, in The history of Japanese photography, ed. by Anne Wilkes Tucker (New Haven, Conn. : London : Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 260-303 (p. 274) ↩

-

Iizawa Kōtarō, “The Girls Are in the Room: Women Photographers in the ‘90s,” in Private Room II: Shinsedai no shashin hyōgen (Photographs by a New Generation of Women in Japan), exh. cat. in Japanese and English (Mito: Contemporary Art Center, 1999), p. 16 ↩

-

Maho Kubota Gallery, ‘Yurie Nagashima’, Maho Kubota Gallery (revised April 2016) <https://www.mahokubota.com/en/artists/yurie-nagashima> [19 March 2018] ↩

-

Bohr, p. 357 ↩

-

In programme mode, the camera automatically calculates appropriate exposure; all that is required of the photographer is to frame the picture and press the shutter release button. ↩

-

“Kayo Ume, Life Cycle”, POCKO <http://www.pocko.com/kayo-ume/> [21 March 2018] ↩

-

Blake Andrews, ed., “Q&A with John Sypal”, B (revised 21 November 2014) <http://blakeandrews.blogspot.co.uk/2014/11/q-with-john-sypal.html> [23 March 2018] ↩

-

Gianpaolo Arena, ed., ‘”Where Now Are The Dreams Of Youth?”’, LANDSCAPE Stories (2016) <http://www.landscapestories.net/interviews/94-2016-yurie-nagashima?lang=en> [19 March 2018] ↩

-

Jennifer Pastore, ed., ‘Yurie Nagashima: And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love’, Tokyo Art Beat (Tokyo: 2017) <http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/2017/11/yurie-nagashimas-and-a-pinch-of-irony-with-a-hint-of-love.html> [18 May 2018] ↩

-

Jennifer Pastore, ed., ‘Yurie Nagashima: And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love’ ↩

-

Jennifer Pastore, ed., ‘Yurie Nagashima: And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love’ ↩

-

Conversations - Artworld Talk - Feminist Aesthetics? Movements and Manifestations [YouTube video], Art Basel, 30 March 2018 <https://youtu.be/hYDAIK7mTaw> [Accessed 19 June 2018] ↩

-

Conversations - Artworld Talk - Feminist Aesthetics? Movements and Manifestations ↩

-

Conversations - Artworld Talk - Feminist Aesthetics? Movements and Manifestations ↩

-

A “Sputnik field” is a field usually created by transplanting ripe crops from a number of fields into a single artificial plot. See Jon Halliday, Jung Chang Mao: The Unknown Story, (New York City: Random House, 2012), p. 520 ↩

-

Dāngdài Zhōngguó cóngshū biānjí bù (ed.), Dāngdài Zhōngguó de Tiānjīn [Tianjin in Contemporary China], vol 2. (Beijing: Zhōngguó shèhuìkēxué chūbǎnshè, 1989), p. 113 ↩

-

Wu Hung, Christopher Phillips, Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China (Chicago: The University Of Chicago Press), p. 15 ↩

-

The Gang of Four (四人帮, sìrén bāng) was a faction composed of four senior Communist Party officials who came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, they were largely blamed for its excesses and prosecuted. ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 15 ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 16 ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 21 ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 21 ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 22 ↩

-

Wu, Phillips, p. 25 ↩

-

Corinne Robins, The Pluralist Era: American Art 1968-1981 (New York: Harper and Row, 1984), p. 213 ↩

-

The Book With a Black Cover was followed by two more books, with a grey and a white covers. ↩

-

Ai Weiwei: Works, Beijing 1993-2003, ed. by Charles Merewether (Hong Kong: Timezone 8, 2003), p. 51 ↩

-

Groninger Museum, ‘FUCK OFF 2. Curated by Ai Weiwei, Feng Boyi, Mark Wilson’, Groninger Museum, (2013), <http://www.groningermuseum.nl/en/exhibition/fuck-2-curated-ai-weiwei-feng-boyi-mark-wilson> [17 June 2018] ↩

-

Groninger Museum ↩

-

Marianne Jacquet, ‘GIRLS by Luo Yang - An Interview’, KALTBLUT. (revised 20 May 2016) <http://www.kaltblut-magazine.com/girls-by-luo-yang-an-interview/> [18 June 2018] ↩

-

Eva Morawietz, ‘LUO YANG GIRLS Ambiguous Identities’, in Girls, (Baden: Edition Lammerhuber, 2017), pp 15-21 ↩

-

Morawietz, p. 15 ↩

-

Morawietz, p. 19 ↩

-

See Annex 1: Interview with Eva Morawietz ↩

-

Morawietz, p. 17 ↩

-

Maximilian Kalkhof, ed., ‘Chinesische Fotografin Luo Yang “Wäre es okay, wenn du dich ausziehst?”’ (21 May 2016) SPIEGEL ONLINE <http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/girls-ausstellung-von-chinesin-luo-yang-okay-wenn-du-dich-ausziehst-a-1093368.html> [15 May 2018] ↩

-

Maximilian Kalkhof, ed., ‘Chinesische Fotografin Luo Yang “Wäre es okay, wenn du dich ausziehst?”’ ↩

-

This and previous quote from Spiegel Online translated from German by Elena Helfrecht. ↩

-

Morawietz, p. 18 ↩

-

Morawietz, p. 18 ↩

-

Patricia Luiza Blaj, ed., ‘Luo Yang’s “GIRLS” Shows The Beauty Of Vulnerability‘, THE OUTSIDERZ (16 March 2017) <http://www.theoutsiderz.com/luo-yangs-girls-shows-beauty-vulnerability/> [15 June 2018] ↩

-

See Annex, Interview with Eva Morawietz ↩

-

Beina Xu, Eleanor Albert, ‘Media Censorship in China’, Council on Foreign Relations (Revised 17 February 2017) <https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-china> [10 June 2018] ↩

-

See Annex, Interview with Eva Morawietz ↩

-

Julian Lucas, ed., ‘LUO YANG: An Exploration of the New Chinese Woman’, Mirrored Society (7 September 2016) <https://mirroredsociety.com/interview/luo-yang-girls> [18 June 2018] ↩

-

Tom Arnstein, ed., ‘Beijing-Based Photographer Luo Yang Shoots to Smash Stereotypes of Chinese Girls’, The Beijinger (27 September 2017) <http://www.thebeijinger.com/blog/2017/09/27/luo-yang-photographer-shoots-smash-stereotypes-chinese-girls> [20 June 2018] ↩

-

Tom Arnstein, ed., ‘Beijing-Based Photographer Luo Yang Shoots to Smash Stereotypes of Chinese Girls’ ↩

-

Clara Hernanz, ed., ‘Luo Yang’s photos show women rebelling against classic Chinese femininity’, Dazed (18 June 2018) <http://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/40161/1/luo-yang-photos-women-rebel-against-classic-ideas-chinese-femininity-ai-weiwei> [19 June 2018] ↩